I’m Melanie Fleming, and I’ve worked at BioWare for almost six years. Currently, I’m a Localization Project Manager, and a gamer. Before my life in the game industry, I was a high school math and science teacher.

Another teacher I know is my amazing friend Mark. I want to share what he and some of my equally excellent coworkers here at BioWare have been doing lately, particularly how they’re responding to the issue of girls and gaming. Mark is a great mentor, and his work is a great example of the simple benefits of human interaction.

Think of a moment in your life when someone transformed from an acquaintance into a mentor. That moment might have been one small word, act, or a sideways look—but it saved you, helped you. If you’re not sure what I mean, please go watch educator Rita Pierson’s amazing TED talk, “Every Kid Needs A Champion”.

Now that you’re thinking about connections and understanding, especially as they relate to kids and learning, let me tell you more about Mark and the Galloway School in Atlanta, Georgia. Mark is a really good teacher, the kind I couldn’t have been in a hundred years. He teaches Grade 3 and 4, so his students are 8-10 years old. Every year, the kids in his class design and code their own video games, all by themselves.

The 3rd graders use Scratch from M.I.T. and talk about variables, loops, input/output, flow charting, and storyboarding. The Grade 4’s used GameSalad to make iPad™ games. The kids create their own game stories filled with ponies, rainbows, robots, space cowboys, and their pet hamsters. They have to think for themselves about how to use and implement each element. Science! Engineering! Problem-solving! I love this stuff.

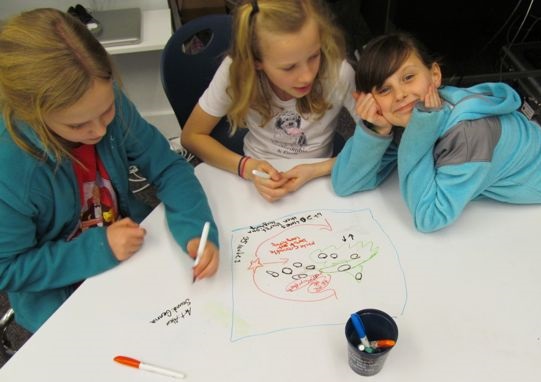

Photo: Students at The Galloway School. You are looking at the future of game design. (Used with permission.)

But my favorite thing about Mark’s teaching is his attitude on equality:

“The more I read about the way women in the gaming industry are treated, and the lack of just decency and respect, the more I want to instill my students that girls are gamers and developers and programmers and that they deserve to be treated just like any other gamer, developer, programmer. The younger I can start instilling that message, the better.”

He pushes back against the superficiality, racism, and sexism the kids absorb through friends, parents, TV, politicians, and our culture generally. In his room, he gives every kid a chance.

But Mark contacted me last year because he still saw a problem. Despite his best efforts, he still found some of his students held the view that “girls can’t do tech”. Similarly, he really had to encourage the girls to “get their geek on”, as he puts it. The video games unit he was doing with them was great, really fun, really instructive—but the bias was still present.

Do you remember what those years were like? That early- and middle-school age is critical. Picture an eight-year-old’s classroom: crayons and juice boxes are still lying around, but there’s also some grown-up, more serious stuff too, as the greater awareness of the world seeps in. If you were into something “different” during that time, you heard the small comments, the teasing. It can be hard not to feel like a freak.

I liked science, but my friends didn’t as much. When you’re the only one in your group willing to dissect the frog, to pour the acid into the beaker, or to build a catapult in your backyard instead of talking about Barbie™ and teen hearthrobs, you can start to feel all alone. The crux of that aloneness is having no positive connections with others who share what you like. The lack of connection is tiring for a social species like us. You have to like your different hobby a lot—a whole, whole lot—just to keep going.

Mostly, I really like our culture. But I don’t like absolutely everything about it, and I feel particularly strongly about this message that girls can’t do tech or science or play video games. It’s a susurrus, constantly whispering to our children. When you’re a teacher, you actually see that influence creep in. Over a few years, you see some of the girls who were good at and interested in math and science steadily and slowly withdrawing from it. Some of the boys grow more contemptuous of girls in technology.

You can label that effect as “nobody’s fault”, but it happens. It is a fault made up of a million small acts. These small biases can grow and grow in people’s heads. How sad it is that, even today, some very vocal folks think it is actually okay to bully, intimidate, or forbid women to do whatever they like with their lives? Their actions may cross a line only years after that bias is first established in their heads.

Mark’s strong philosophy on classroom equality assumes the issue isn’t only about the girls OR the boys, but both. He sees himself in a race to instill a good sense of equality and fairness in his students before they absorb and believe too many of our culture’s more archaic ideas on race, sex, and status. For him, for any teacher, the key to this is connecting strongly and positively with his students and making that difference in their lives.

When I taught, connecting with my students was closely related to my personal discovery of what made each person unique. I loved that part of teaching. Kids might do nine out of ten mundane things exactly like their friends, but the tenth thing is something totally new and interesting, a flash of something that is theirs alone.

These connections can be unexpected and amazing. One year, I filled in on an English course for a semester. I especially remember one girl in my class: 15 or 16 years old, same hairstyle and shoes as everybody else—just one normal student in a class of thirty-two. A bit invisible, innocuous, shy, often absent. When she is there, she often appears disconnected, bored. She’s always in the back row, and she stares out the window a lot.

I’ve spent several reasonably frustrating weeks of effort to engage with her (when she actually attends). Then comes the day to hand in midterm projects: she walks up and hands in a beautiful and quite gigantic report. It thumps when it hits my desk.

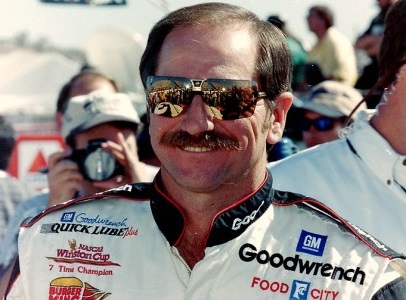

Her report was about NASCAR and her love of racing really hot stock cars. It detailed her idolization of Dale Earnhardt, Sr., and how sad she was at his tragic death. It was well-written. It had pictures and diagrams and charts. It was an awesome report.

She lived in northern Ontario, Canada, where NASCAR is rare at the best of times: Hockey was big. Curling was big. Figure skating. Moose-tipping and snowmobiles and boating and lakes. But NASCAR? Wow.

This was the most communication I’d gotten from her ever, and it was so real and honest. Moments like that are why people become teachers—do you see? It was that connection she offered to me.

So after class, I talked with her about her report, mostly because I was so blown away and interested, but also because I was a youngish teacher, a bit suspicious, and checking to make sure it was actually her work.

And she started talking about it. Talking and talking, like a dam breaking. As the words spilled out of her, her hands gestured broadly, the fingers spreading and closing and waving about in the classroom sunlight like little angel wings. I was astonished.

From her mouth tumbled facts and figures and the technical specs of her favorite car. She explained what a championship was, the Daytona 500, and what “The Golden Age” meant for stock car racing. A whole sport I knew nothing about was all bundled up in her head.

More than anything, I was touched by her sharing something with me that she obviously cared so deeply for. (There were tears in her eyes when she talked about the big crash in Dale’s last race.) It was so brave and earnest of her, to give this to me, a teacher who’d nagged at her just the day before for skipping yet another class. Because of her, I still remember that Dale Earnhardt, Sr. won seven championships in racing and that he drove a car with Number 3 on it.

Note: If you’re wondering, this is Dale Earnhardt, Sr. (Source:en.Wikipedia.org)

Despite my joy at her passion, I remember thinking it was odd that she had such a liking for the topic. But I admit our northern climate wasn’t really behind my wonder at her hobby. It wasn’t because she was the only one in her class with this love. To my shame, I realized my surprise and delight really stemmed from her gender. This girl liked cars.

I have always thought of myself as a feminist, progressive, fully unstoppable—and fair. If a male student had turned in the same report, I would absolutely have given it the same high grade because of the exceptional effort it represented. But I wouldn’t have found it surprising for a boy to like cars.

Now I’ll ask you a somewhat personal question: Would you have found it surprising?

Right then, I realized there was an assumed difference between boys and girls in my head, and that’s called a bias, my friends. Maybe it’s a soft one; I wasn’t spouting vitriol on the internet or bullying her, but my feelings of surprise meant a bias existed, culturally ingrained in me from such an early age that it was hard to even be aware of it. I felt a bit silly and corrected my thought: Yes, teacher, you idiot, girls can like cars.

This may seem like a small moment, barely worth mentioning. But these little check-in moments with yourself are important. We can’t help our thoughts, but maybe not every thought we have is worthy of us. If enough of us fight against the biases in our own heads, maybe yucky thoughts like “girls don’t like cars” will fade completely in a few years or a generation. Hopefully soon, it won’t be rare for a woman to like cars, to get a job working on them, to race them, or to engineer new and better ones.

Am I fussing needlessly? Consider that in 2012, women made up only 1.8% of automotive body repairers, and 1.2% of automotive technicians and mechanics in the United States.

Over 98% of North American auto body repairers are men. There’s no reason women shouldn’t repair cars, yet they don’t. Isn’t that weird? Sure, maybe plenty of women don’t want to fix cars as a career, but as girls grow up, shouldn’t we at least give them a real chance to find that out? I think our small moments with each other are the most important factor in changing this.

As I sat with my student, connecting with her over this report in a short moment between classes, I had the opportunity to choose how I act. It would have been a mistake to show her my surprise or make a big deal in front of her friends about the fact she likes cars. I didn’t have to make her feel weird about it. I could be a mentor. I could connect, and make her feel less alone.

So I praised, gave her a good grade on the paper, and was so touched that my small words of praise didn’t feel like enough in return for her gift.

Now, back to video games. Mark’s email arrived in my inbox as we were getting ready to launch Mass Effect 3 last year. He asked for BioWare’s help with the gender equality issues he’s seeing in class. His logic was that if the boys and the girls could just see some gaming professionals who were women, it might start to combat these stereotypes the kids had absorbed.

At first, I wasn’t sure if it would do any good. “How can I inspire a kid who doesn’t know me and has never seen our games? They aren’t even old enough to have played them.” But after talking to some women around the office, I wrote Mark back and agreed to do it. Maybe our small act would help even one kid.

So I gathered up some BioWarians: a level designer, a cinematic designer, a programmer, a writer, a producer, quality assurance testers, an editor, and a voice-over director. I worried I’d have to convince busy women, but my fabulous coworkers jumped in with great enthusiasm.

The session was simply an hour-long Skype session framed as a Q&A. We fielded a couple questions about gender, but the students—both boys and girls—mostly asked good general questions about the game industry. Some students from higher grades were interested and dropped in, as well. For many, we were the first game designers they had ever met. I felt good that, at the very least, each of those kids now knows a) my profession exists, and b) both men and women can work in it. The best part was the strength of our interactions with the students in only an hour of real time.

Mark said the comments about it from his class went on for months. A couple of boys actually made me a gift and nagged Mark until he gave in and mailed it all the way across the continent to me. It’s awesome. I think it’s maybe a wooden see-saw or a ramp or something. The boys nailed it together and painted it green and stuck Mass Effect stickers on the top. Those orange things stuck to it on the side are omniblades. It is the weirdest thing I’ve ever received, completely original, and I love it:

We’re thrilled that the BioWare sessions with The Galloway School are now recurring events. Just this past March, some female producers, programmers, and designers met with Mark’s classes again. We were peppered with enthusiastic questions:

- “What do you think is best part of game design? Who was your greatest motivator?”

- “When you started making games, was your first game harder than other games afterwards?”

- “What does it feel like to finish a game?”

- “Mr. Gerl says we need to do stupid flowcharts. Do you REALLY need to do all these storyboards and flowcharts and things?”

Photo above: Some of the awesome women of BioWare, during our seminar with The Galloway School in March 2013. From nearest to farthest, we have Karin Weekes, Teri Drummond, Susanne Hunka, Brianne O’Grady-Battye, Melanie Faulknor, Catherine Lundgren.

Our connections with the kids were positive—everything that makes me appreciate my coworkers and look toward the next generation of young people with hope. Mark tells me this year’s class went further and created their games using working controllers made of sensors and LEGO™ pieces incorporated into their designs.

Next year, I’ll ask Mark if both female and male designers can participate in our sessions, because we have guys here who are also passionate about equality in the gaming industry. I’d love for the students to hear their opinions, and for the guys to share in the special connection we have with Mark’s class. More than ever, this experience convinced me that heroes and mentors can be anybody. Our small connections are important. Everything we do and say matters to someone, somewhere.

Photo: More of the awesome women of BioWare, during more of our session from March 2013. From left to right, we have Angela Penner, Vanessa Potter, Vanessa Alvarado, Karin Weekes, and Liz Lehtonen. I have no surviving photo from the first session we did last year, but at that time, we heard from Janice Thoms, Kris Schoneberg, Sarah Hayward, Caroline Livingstone, and Sylvia Feketekuty. Yes, that is a mural of the Illusive Man on the wall in the background.

Thank you to the wonderful students at the Galloway School for speaking with us. Thank you to my heroes at BioWare who mentored and participated in these sessions, and a special thank-you to Mr. Mark Gerl. Without him, none of this would have happened, and our BioWare lives would be poorer for it.

Melanie Fleming

Project Manager, BioWare