Dragon Age: The World of Thedas – Volume 2 has been out for a few weeks now and the reception to the book is overwhelming to say the least. The exclusive edition is sold out. The regular edition is already in its second printing. Fans have made recipes from the book and sung lullabies. We even tried our hand at a couple recipes ourselves, with questionable results.

Today, we’re thrilled to present another short story by Joanna Berry. Last month, she gave us a glimpse into Samson’s past with Paper & Steel. Now, we learn a lot more about Calpernia, the Tevinter mage who rose from slavery to become leader of Corypheus’s loyal cult, the Venatori.

Calpernia crouched and laid her hand on the pitted flagstone. Yes. Here. In this spot, when she was seven years old, she witnessed a man turned to dust by magic.

Even now, the stone held a trace of power. She used her own magical talent to draw upon it, and her own memory. The moment returned to her: the man’s shriek as his body turned to sparks and ashes, and then into nothing at all. She could remember the horrified murmurs from the crowd, and the cowled mage who cast the spell stalking away.

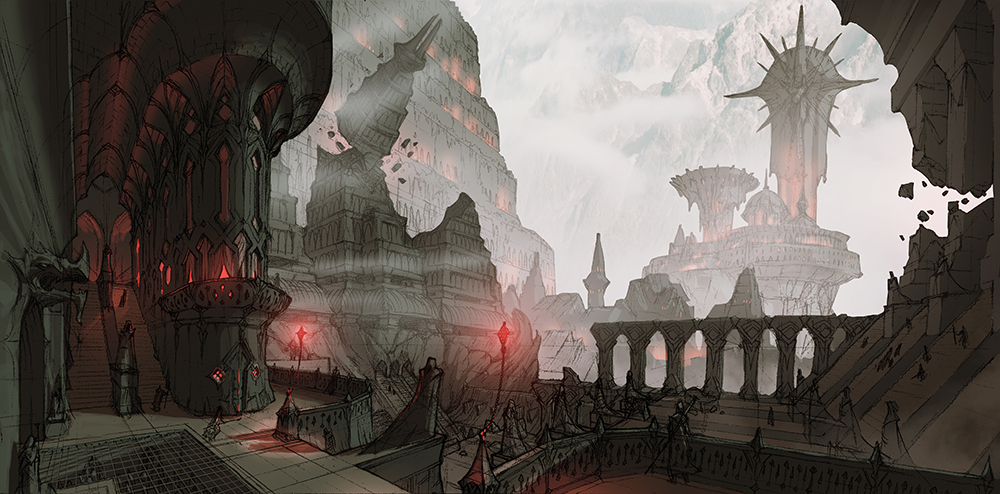

Later, she learned such magical duels weren’t uncommon on the streets of Minrathous, capital of the Tevinter Imperium. But it was the first Calpernia saw with her own eyes.

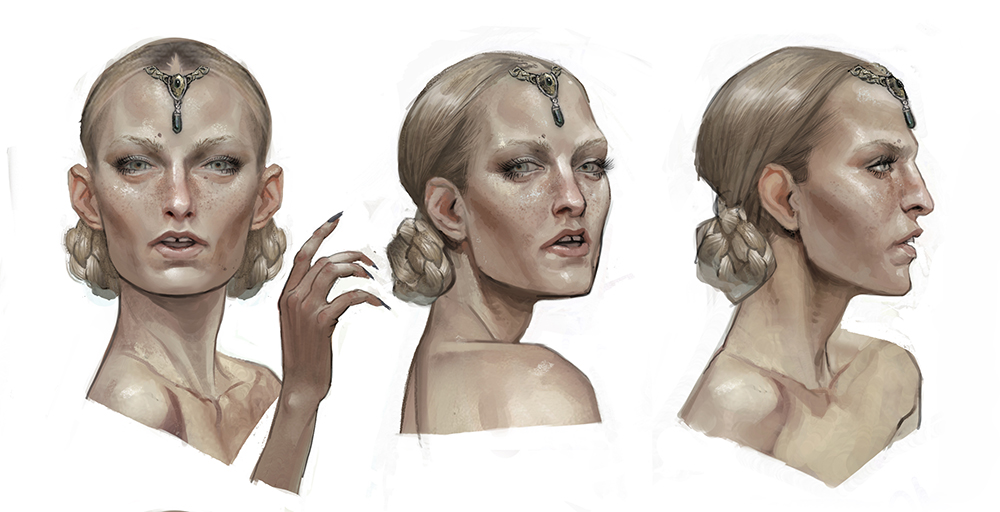

With her hand still upon the stone, Calpernia dug further into that fading scrap of power, wanting to feel like the child she had been: a blonde girl as skinny as a bundle of sticks with a rag tied on one foot instead of a shoe.

She had come upon the duel on her way back from the market, carrying a bottle of thick, soured milk and a jar of olives. The shouts and the thunder drew her to the edge of the crowd, but she didn’t share their fear. Unblinking even as the nameless man’s screaming face blew away on the wind, it was her first true glimpse of power.

A light sparked in her then, a feeling that brimmed to overflowing. The bottle of soured milk smashed on the ground, the olives scattered, and she fled, not from fright but something too tremendous for a little girl to understand. She darted through the city into a district she barely knew.

“Where I first met the ferryman,” Calpernia said aloud, now lifting her hand from the flagstone. “And now, to say goodbye.”

She went to dust her palm on her clothes, then caught herself. Instead of rags, she was wearing a fine robe of embroidered blue and black linen. The black sash that wound around her narrow hips hid a small purse of coins. She carried a blackthorn staff in her free hand, and on her feet she wore soft kidskin boots. The generosity of her Teacher had given her this ensemble only days ago, and she wanted to keep it all pristine. She’d never owned anything before.

Calpernia rose and continued walking. No one had given her moment of reflection a second glance. The narrow street, its marble crumbling like old bone and littered with rubbish, was one of the quieter avenues in Minrathous. The few that passed—elves bent under heavy packs, soldiers whose spears and armor winked in the sun, a stout robed priest—had better places to be.

So did Calpernia. She might need to leave Minrathous any day now, at a moment’s notice. If she was to say goodbye, it should be done properly.

Following the street and its twisting alleys, she came to the market in Three Imperators’ Square. The three statues that gave the square its name posed around a sluggishly-trickling fountain in the center. Calpernia followed a sweetly-fragrant breeze through the crowds of citizens, street performers, and traders to a stall that carried perfumes and incense. A pack of filthy children harassed the incense seller, begging for coins; one boy yelped as a piece of charcoal shattered near his bare feet.

“Be off with you,” snarled the incense seller, brandishing another chunk, and the children fled. “Blighted refugees won’t take to be told,” she added as Calpernia drew closer, then broke out a sweet smile. “Your pleasure today, my lady? Jasmine oil for your beautiful hair? Or this rare attar of tahanis, brought for you from the savage jungles of Par Vollen?”

Blushing, Calpernia looked over the stall and all its scented luxuries. She could buy the jasmine oil, she realized, or any one of these jewel-like bottles, and it would belong to her forever. She could go to another stall and buy sweet dates, and sit by the fountain to eat them; she could spend all day in a bathhouse; she could buy passage on a ship and sail away to warm, distant seas. She could do anything she wanted.

Marius, if you could see me now.

Calpernia steeled herself against that thought. She had dreamed enough of the past today. To business.

“I need incense,” she said. “Olibanum resin. It’s for… an old friend.”

The incense seller raised her eyebrows and went to a small locked chest behind the stall. “My lady has exquisite taste. How much?”

“Enough for an offering,” said Calpernia, then, giddy with the chance to own something: “A generous offering.” The ferryman had earned it.

As the seller measured out the resin, Calpernia looked around the market; past a juggler tossing painted wooden staves, a group of poorly-dressed figures limped through the market, laden with heavy bundles and staring with frightened eyes. People jeered.

“So many refugees in the city these days,” the incense seller said, following her glance and putting a weight on the scale. “The Qunari have made another push.”

“It isn’t right,” said Calpernia.

“Oh, certainly! We could do without more beggars on the streets….”

But Calpernia was looking not just at the refugees, but the lichen-stained, crumbling stone of the square in which they stood, and the aging towers of Minrathous rising beyond. She thought of the Qunari harassing the coastline with their dreadnoughts, of the once-mighty Imperial Highway that Tevinter had used to cross a continent. It was now little more than a broken line of marble, overgrown by the countryside. “Citizens of the greatest empire in Thedas, reduced to rags by barbarians,” Calpernia said softly. “All that Archon Darinius made, come to this. Our cities were mighty once, our reach so far. Those days should come again.”

The incense seller blinked, and Calpernia wondered if that wasn’t how free citizens spoke. To smooth things over, she took out her purse and handed the seller several coins. “My incense?”

The seller looked at them. “Half as much again, please, my lady. Olibanum comes dear these days.”

Calpernia’s smile fixed; she hadn’t known how much it would cost. Deliberately, she placed coin after coin in the seller’s palm. “My usual supplier is less costly,” she said, accepting the little pouch of incense with what she hoped was appropriate dignity.

The incense seller bowed. Calpernia turned away, a flush on the back of her neck. Still, the seller had been polite, despite the confusion. She’d seen Calpernia as a mage, and behaved with the proper deference.

A mage, Calpernia thought, and straightened.

She crossed the market to the western arch that led farther into the city. Two magisters were blocking the way, talking with furrowed brows while their entourages of slaves and bodyguards stood, attentive, to one side.

As Calpernia drew close enough to see their faces, one of them glanced in her direction. Her heart raced; she changed direction without breaking stride and headed for another side street. Safely away, she glanced over her shoulder. The magister on the right, a muscular man in a silver-grey robe, had a distinctive burn on his cheek, almost like an inverted question mark.

It was Magister Anodatus, a man she knew better than she’d like. He was descended from Archon Ishal, and his family was traditionally responsible for the upkeep of the great Juggernaut golems that stood, long silent, outside Minrathous’s gates. They even got a stipend from the city coffers for it. But Anodatus seemed to think the money was better spent on lavish parties, gambling, and dwarven-made trinkets. Calpernia knew this because she had served mint tea to him and his latest simpering consort, stood and listened while he boasted, or made herself smile when his “wit” struck like a scorpion.

Thus, even dressed as she was, with her blonde hair styled, her face painted to accentuate her soft hazel eyes, Magister Anodatus might recognize her as a slave.

He would want to know what had become of Calpernia’s master.

Calpernia went in the other direction. It wouldn’t do to keep the ferryman waiting.

* * *

Calpernia was put on the slave markets when she was old enough to stand upright. Her earliest memory was of being pressed on all sides by bodies—everyone sweating and crying—until she was expelled first onto the auction block and then into her first household. She served belowstairs, usually on her hands and knees with a scrubbing brush, while she was still small enough to crawl into chimneys and under floors. She learned to listen to echoes through the walls: stories, scandals, and confidences.

Some cellars in Minrathous connected to the ancient catacombs carved out of the bedrock beneath the city. No one knew how far they ran. The air that came up from those places smelled old and had its own secrets. Once, while sweeping the wine cellar, little Calpernia found a deep crack in the flagstones between two looming barrels. She could feel air stirring out of it.

Putting her small ear against the crack, she heard something echoing from far below—a song, a sob, or a whisper, too distinct to be the wind and too eerie to be human. It lingered in her dreams long after.

Time passed, as she toiled in kitchens and attics or under the hot Minrathous sun. Calpernia was sold on from place to place as she grew from a skinny girl into a slim young woman, often ignored, more often whipped. She bore the scars with an angry pride but knew it could have been much worse. Something about Calpernia made her masters uneasy, and it stayed their hand when they could have lashed her senseless. Instead, she was the one ordered to run errands in the more unsavory areas of the city, clean mysteriously-sealed rooms, or take messages after nightfall out past the Proving Grounds.

She went cautiously but without arguing. Calpernia didn’t fear darkness or whispers from empty rooms—nor, in time, the strange dreams that came to her.

The other slaves weren’t as accepting of peculiar things.

“You were talking in your sleep last night,” a kitchen girl accused her one evening, as she returned to the quarters exhausted and footsore. “Weird words. Not Tevene.”

“I… Maybe I was. I don’t rememb—“

“It’s not natural,” one of their master’s bath attendants added, folding his arms across his massive chest.

“But I can’t help what I dream!”

“You can help where you dream,” someone else said. “Go on out into the stables. We don’t want that in here.”

She went—and huddled in the straw while the tears in her eyes stung worse than any whipping. She had no family, no house, no one in the world but her fellow slaves. And they didn’t even seem to realize their importance. On her errands, she saw how slavery was the blood and breath of Minrathous, even while many slaves, in their despair, stopped thinking of themselves as people. Some stopped thinking at all.

She would have said more about it in the quarters, but they stared at her instead of listening. Whatever strangeness her masters sensed about her unsettled the other slaves, too.

Eventually Calpernia was sold again. Her last mistress must have called in a favor because she ended up in a magister’s household.

For a slave in Minrathous, that was a fate which could go either way. On the one hand, magisters lived well enough that their slaves could enjoy a better class of scraps. On the other, it was whispered that some magisters preyed on their slaves to fuel blood magic rituals.

With her head full of such stories, Calpernia tiptoed into Magister Erasthenes’ home like a fearful cat. Thankfully, her new master was no blood mage, but a scholar specializing in studies of the Old Gods. Erasthenes’ vast, un-dusted mansion was littered with books and ancient relics. A cracked dragon statue, which stood outside the Temple of Razikale before it became a Circle, rested in the foyer and loomed at visitors.

There were few other slaves in the house, meaning Calpernia found herself cleaning and fetching and scouring from dawn to twilight. Erasthenes wasn’t all that old, but his lungs and back were bad, so most of his time was spent shut up with his relics or doing rites with his colleague, that boastful Magister Anodatus with a scar on his cheek. The worst beatings—given by Sorka, the household’s grim dwarven steward—were for disturbing his work, which would be easier to avoid if Erasthenes didn’t leave it littered about the place.

One afternoon, carrying heavy buckets of water across the courtyard to the kitchen, Calpernia’s arms ached too much to keep going. She set the buckets down and leaned against the wall to catch her breath. Her eye fell on the door to the antechamber, where she’d been told the slaves were not to go. But if she slipped through, she could cut across that wing and take the service corridor to the kitchen, rather than carrying the buckets all the way around.

Biting her lip, she eased the door open and peered inside. No one was in sight. Long shadows fell on a marble floor as smooth and cool as cream.

She was sweaty from the heat. Calpernia ventured inside, sighing in relief, then paused. The floor’s perfection was broken up by strange symbols painted across it in rose and silver.

Crouching, she reached out to one of them, a—

“Careful,” a voice warned her. Calpernia’s heart stuttered.

One of the mansion bodyguards was standing at attention against the opposite wall. Unlike most of the hulking brutes who escorted magisters across the city, he was young and comparatively lean under his armor, with short brown hair cropped close to fit under a helmet.

He nodded at the symbols. “Wards left over from one of the master’s experiments last night with Magister Anodatus. I wouldn’t meddle.”

Calpernia straightened, smoothing herself down. “I know you,” she said, needing to say something to calm her racing heart. “You’re Marius. You broke that thief’s wrist last month.”

“He’ll live,” said Marius, “which is more than you’ll get if you touch those damned magic signs. Watch your feet.”

Calpernia looked down at the symbols again. Magic. The power she’d seen as a little girl, the power of the Magisterium. This was the root of it all. The elegant signs seemed to dance across the polished surface. “Even if they are a threat, they’re lovely,” she murmured.

“Lucky not everything lovely is dangerous,” said Marius. Calpernia’s head jerked up to see the ghost of a smile on his face. Did he—?

Marius glanced around, then opened the door beside him. “This is the shortcut you want, right? Go on. I won’t tell anyone.”

Calpernia retrieved her buckets and went past him. “Thank you,” she said, “and thank you for the warning, but…“ She glanced at those large hands that had snapped a thief’s arm. “I have no fear of dangerous things.”

Calpernia smiled as she left.

After that, she began to see Marius about more often. Or perhaps she simply came to notice when he was there. Marius served as a guard for the house and Erasthenes’ person because there were so many ancient relics here, but his natural skill and speed far outstripped that of a simple bodyguard. Calpernia spotted Sorka, the steward, watching Marius’s training regime sometimes, her thick arms folded and her brow furrowed in calculation.

Slowly, Calpernia’s caution at living in a magister’s house was replaced by curiosity. She began to steal looks at her master’s tomes while she dusted them. In time those glances became longer. Letter by letter, word by word, she began to teach herself to read from them, respecting the power that reading gave her masters.

The books were wise and generous friends. They became good company when she needed it. Though she tried to reach out to the mansion’s slaves, she was shunned again—for her dreams, for her ideas—by everyone.

Almost everyone.

“No one listens to me,” she said late one night in the library, turning through a dusty grimoire full of long words she couldn’t decipher yet. “We slaves barely listen to one another.”

“I listen to you,” Marius pointed out. He was standing guard at the library’s door, though perhaps he wasn’t standing on the side Sorka had meant. “Only a fool would ignore such a sweet voice.”

Calpernia flushed and kept turning the pages. “Flatterer.”

“You expect too much of the others. You use the name Calpernia, and tell people who wear rags and sleep in corners that they’re the most important people in the empire. What should they say?”

“They shouldn’t say anything, not with Sorka’s eye on them. ‘In silence is the beating heart of wisdom’.” That, from the verses of Dumat, was Calpernia’s favourite sentence so far. “Just recognize how valuable they are, even as slaves, and what they could do if they were free. Open their eyes.”

“To see what? Old palaces and rotten mages who pour out slave blood like water? Even that ferryman of yours—”

Calpernia rounded on him. “It doesn’t have to be this way!” She dropped a fist on the grimoire. “The empire used to be different. When a person’s life was spent, it meant something—it bought something. If slaves had a voice the Archon could hear…”

She trailed off, searching for the words, and Marius’s face fell. “I’m sorry.” He sighed, and offered a smile. “Would you read one of the books for me? Nothing about mages this time.”

“I don’t think this is a storybook.” Calpernia pushed the grimoire back, rubbing at her aching neck and stretching, and found herself staring up at the ceiling of the library. Normally she was focused on dusting; she’d never looked at the ceiling before. Dark blue lacquer covered the underside of the dome with the constellations picked out in gold leaf. A knot of gilded glass marked each star.

“Here is a story then,” she said, still leaning back and looking at them. “A girl is so bent over her work she has forgotten how to look up. Everyone she knows has forgotten, too. The stars are there, but she doesn’t remember why they are worth looking at.”

A shadow blotted out the constellations overhead. She blinked as Marius leaned over her. His breath smelled sweet. He took her chin in a gentle hand and tilted it up.

“Skip to the ending,” he told her.

She ran a finger down his cheek and rested it against his lips. “It ends in silence.”

The candle on the table beside them guttered and went out.

They were as discreet as they could be. But Marius’s talents were drawing more and more attention. Even Calpernia saw he was wasted as a bodyguard. With the right training he could become a talented assassin or even a mage-killer: a source of prestige for any magister and a way to tip the political scale. But she told herself Erasthenes didn’t care about such things, only his work. It would be all right.

When it happened, it was painfully quick. Calpernia came home from the markets shouldering a bag of vegetables to see Erasthenes speaking with a stooped but powerful man. Even in her exhaustion Calpernia knew Nenealeus the trainer, the one who honed the finest fighters in the city—if they survived. She knew at once for whom he had come. Dumping the vegetables in the kitchen, she raced through the mansion, from room to room, her eyes becoming more frantic as she realized Marius was already gone.

There were no goodbyes. Coin changed hands, a ledger was signed, and it was done. Calpernia looked for Marius’s name on the roster each time Nenealeus’s slaves posted it in the marketplace, but she never saw it. When rumors of his fate crisscrossed the mansion, she couldn’t bear to listen. She refused to imagine a riven helmet or blood on the hot sand of the training ground.

She’d seen fellow slaves sold unexpectedly or killed before, Calpernia told herself. The same story played out every day in Minrathous. But instead of placating her, the thought—that this was all commonplace—festered. Her tears, such as they were, dried up.

Needing solace, she began her secret visits to the library again, but they gave her no comfort. One night, trying to sound out a word she’d never seen before, her thoughts stuck in her mind until the anger in her chest bloomed into a suffocating ball. Enraged, she slammed the book shut.

It burst into flames.

Her scream, which woke the house, was only partly from shock. The rest was exultation.

Magister Erasthenes had her summoned the next morning and frowned at her, owl-like, for several minutes. Calpernia knelt in front of him clutching the ruined book. Last night’s delight—power, power at last—had been replaced by fear. A slave with magical talent needed training or their owner might find an abomination, frothing and shrieking in the slave quarters one day. But as Erasthenes often murmured when they were cleaning his rooms, he couldn’t bear distractions. He might simply sell her. Or use her as an experiment.

Calpernia looked up at him, knowing that as far as Erasthenes was concerned, her life-changing moment was just another thing to keep him from his books. She could feel, as never before, that her very existence was in someone else’s hands, and they could simply throw her away. Perhaps Marius had felt the same.

Eventually, Erasthenes sighed and spoke to Sorka, over Calpernia’s head: “I suppose I’d better start with the basics.”

Calpernia smiled, with relief, for the first time in weeks.

From Erasthenes, she learned to master her powers, eagerly testing the limits of her strength while she sparked fire in the palm of her hand. Oddly enough, with her magic known, the other slaves warmed to her. While before she’d just been strange, a fear they could name was one with which they could live. Calpernia slept in the slave quarters again, and slept well. When she talked excitedly over their evening meal, a few slaves drew their stools closer to listen.

But once he was certain she had her magic under control, Erasthenes went back to his study and shut the door. Calpernia was left with a broom in her hand instead of a staff. What did Erasthenes care? He had his peace and quiet.

Hungry for something more, anything, Calpernia secretly returned to Erasthenes’ books on ancient Tevinter and the Old Gods, but now with deeper understanding. There was always more. When out in the city on errands, she would visit the ferryman, and pour out her learnings to him: epic poems written to honor Urthemiel the Dragon of Beauty, campaigns of long-dead imperators, the Imperial Chant of Light.

But her hunger still went unsatisfied. That Erasthenes was a temperate man made things worse. If he had viciously beaten or humiliated her, Calpernia would have had somewhere to direct what burned inside her. But Erasthenes wanted only to potter about his relics or study with Anodatus, oblivious to everything else.

The more she learned of Tevinter’s history, the more she began to see the same indifference everywhere in modern Minrathous. At least slaves had good reasons to be preoccupied. The Magisterium chased petty grudges, forgetting that Minrathous’s walls still had cracks from the last Qunari assault; the great Juggernaut golems Anodatus was meant to restore were silent; and their empire grew moss between its flagstones. But what did that matter, so long as this week’s rival was humiliated? The greatest empire in Thedas, forged by ancient heroes, and the Magisterium took it for granted. They did not pay for what they had.

You’re mages! Calpernia wanted to scream when Erasthenes invited visiting scholars or his peers over to drink fragrant tea, play chess, or gossip. The ancients built the greatest empire in Thedas with wisdom and conquest! Now the only ones who must sacrifice for Tevinter are slaves, while you spend all your time on… frippery! The Chant was right. When you can do anything you wish, why do you do nothing?

“This is the one?” Magister Anodatus asked Erasthenes one afternoon. As Calpernia leaned over to refill his teacup, he grasped her chin. “She seems half-broken. Hardly bows to her betters—and those insolent eyes. You should send her to the Circle. Her… attributes might buy you some influence at least.”

Calpernia froze —by “attributes” she knew he meant the blood of a slave capable of magic. Anodatus yanked her head from side to side, studying her. For a second she was reminded of Marius in the library; but even the sting of that memory was nothing beside the humiliation. Slaves were pawed all the time, but grabbing her in front of her master like this was…

“Leave the poor girl in peace, Anodatus,” Erasthenes said, waving a hand. “Calpernia, bring the pastries.”

Anodatus let go, smirking. Calpernia willed her face blank and sank her nails into her palms.

Alone on her pallet that night, her face well-scrubbed where Anodatus had touched, she looked at her scarred, roughened hands. She had vast magical talent, she knew, running as deep as the catacombs below the city. But it wasn’t enough. In Tevinter, true change would take political power as well as magic. She was willing to earn that power, to give people like her some path upwards, if only Erasthenes would take her as an apprentice. But when she tried to frame the words, he gave that owlish frown and turned back to his books. She was only his slave, after all.

Calpernia despaired. She daydreamed of escaping into the city on her next errand. But a runaway slave with magic in Minrathous would be hunted down in days. And it would be the same anywhere in Tevinter. If she was meant to achieve anything beyond a life of drudgery, she had been cheated of it simply by being born so low. Just like every slave she had ever met.

Her tale might have ended there. She might have given up altogether and become another dead-eyed laborer with her magic withered to nothing. But her Teacher came, and everything changed.

She’d spent that day helping to carry heavy sacks into the cellars. After she fell into a dead sleep from exhaustion. But when she woke in the middle of the night she sat up clear-headed, feeling a strange presence in the house. Calpernia had felt great power before, when Erasthenes performed intricate spells as part of his research. But this was of another magnitude entirely. It was a high, trembling feeling that plucked her out of bed at once: go and see, go and see.

She pursued that feeling through the dark house as if she was following a lantern. Hearing voices from the foyer, she peered around the door. Moonlight fell in a shaft on the great dragon statue. Erasthenes crouched awkwardly at its feet, facing a gaunt figure wrapped in a dark blue cloak who towered over him.

“…as I have heard,” the figure was saying in a soft, guttural voice. “But any relics of Dumat are mine to claim. You dissent?”

Erasthenes made a wheezy sound. Calpernia gulped, and the figure looked directly at her. Under the hood she saw his eyes: one the color of dark amber, and the other mercilessly pale, set in a hideously scarred visage. But Calpernia had lived in Minrathous all her life. She’d seen magical deformity before, some of it self-inflicted.

Calpernia stepped out and stood before the visitor. As if able to see herself through his eyes, she felt like a clear white flame, casting back glaring shadows from everything she passed.

“Calpernia, you are called,” he said.

She stared, wondering how he could possibly know her name. Eventually the visitor nodded. “In silence, the heart of wisdom is found. You know this already, I think.”

Calpernia blinked at that phrase, and then bowed as she had never done for visiting magisters. In the corner of her eye she could see Erasthenes staring, voiceless.

“I came for relics undeservedly owned,” the visitor continued. “Yet I find more potential than I imagined possible in this time.”

He passed a hand close to her face. Calpernia flinched, but he didn’t touch her. An odd smell clung to his skin, like long-dry carrion overlaid with dust and spices. “Power immeasurable. A champion, perhaps. Yes. You would follow, if I asked it of you?”

“Follow you to where?” she asked, fascinated.

“To forge a better world than this.” The visitor looked up at the dragon statue almost piously. “This place is half sacred to the gods already. I claim it, in their name. And this poor curator,” he added, looking at Erasthenes now. “Where better for the remaking of Tevinter to begin?”

“The… remaking? Of the empire?”

“This is no empire,” the visitor said. “Not compared to what was. Not yet.”

Calpernia looked at her old master cringing on the floor. His eyes bulged with fear. She felt a pang, but her scorn was stronger than her pity. Erasthenes had magic, wealth, a place of privilege—and Tevinter was no better off than if he’d never existed at all.

She turned to the grim, terrible figure before her and said: “I will go with you.”

“I have sanctuaries in the city,” he later told her, when she’d begun to think of him as her Teacher. Already he’d taught her feats of magic that far outstripped Erasthenes’ little lessons. His power was immense. She was beginning to comprehend how this man had cowed Erasthenes—a magister of no small power—in his own mansion with barely a word, and she longed to learn more. “My servants will see you fittingly attired before we leave. A slave you are no longer, but my lieutenant and pupil. My loyalists, the Venatori, gather in secret awaiting our day of glory. Prove yourself, and you may rise to lead them, as befits your power.”

Her heart swelled so much her ears hurt. It took her a moment to realize what else he had said. “Did you say ‘leave’?”

“Much there is to do elsewhere. I must be gone tonight. Complete the business I have in the city, and follow when word is sent. We will speak more of your role then.”

“I have… I have business of my own, too.” The other slaves had fled the mansion before she could speak with them, and Marius was gone, but the ferryman remained. It was sentimental, perhaps, but she wanted one proper farewell in her life. “I want to say goodbye to an old friend.”

Calpernia expected her Teacher to mock her, and she had a fierce retort prepared. Instead he said: “Leave no regrets.”

She didn’t ask what he had done with Erasthenes.

Her Teacher’s business was conducted quickly. She visited a number of houses in the city where Venatori loyalists dwelled, and was presented with gifts for her Teacher at each one: thick letters with a strange seal, runes, mysterious elven-looking maps, and a heavy pouch, its laces sealed with lead. She accepted them graciously.

Less gracious were a few of those whom her Teacher had described as the Venatori leadership. At their homes, Calpernia perched on the edge of a chair, sipping tea or nibbling fragrant pomegranate seeds—sweeter than anything a slave could imagine—enduring elaborately-veiled barbs that reminded her of Magister Anodatus. She realized quickly that they were not going to accept her as a fellow Venatori, despite the favor of her Teacher and her sheer magical talent. They would need to be handled. Remembering the bloodier tales she had read in the library, Calpernia drank their tea, smiled politely, and seared each name into her memory.

But the rest—scholars, philosophers, hunters to be—these men and women, pillars of the empire, bowed politely in her presence and spoke to her as an equal. Calpernia, standing straighter than she ever had in her life, answered as formally as the heroes of Tevinter legend. These Venatori saw the cause, and the stakes, as clearly as she did—they were what Erasthenes should have been. In her Teacher, they saw a being possessed of not only immense power but also divine purpose; Calpernia had witnessed his wisdom and providence for herself already. With the Old Gods gone and the Maker silent, it would take a god’s strength to reshape this world. Calpernia knew that kind of strength was within his grasp.

Though she and the other Venatori only stood on the verge of Tevinter’s rebirth and her Teacher’s final apotheosis, Calpernia felt great meaning in each word exchanged. Freed, she felt great meaning in everything.

* * *

Now, away from Three Imperators’ Square with her olibanum resin, the day was hers. Only the sight of Magister Anodatus, that scarred old goat who had the nerve to grab her face over tea, had soured it.

Calpernia turned down the long avenues of Minrathous, hearing the cry of sea birds and the ring of hammers from dwarven merchants. Her packet of olibanum resin was tucked safely into her sash. Its delicate fragrance mingled with the other scents of the city: smoke, the salt of the ocean, baking bread, filth from a nearby sewer, and sawdust from the shipyards.

As Calpernia crossed to the western side of the city, a new smell came to her on the breeze: flowers and greenery. She turned a corner and saw the gigantic Proving Grounds at the heart of the city, where warriors fought for honor and glory. The building was shaped like the prow of a ship, dwarf-built of dark stone with lush terraced gardens cascading down the sides. As always, crowds jostled at the entrances to hear the roar of victory. White birds wheeled overhead.

The sight of it touched Calpernia’s heart. Then her head turned; she spotted a silver-grey flicker in the corner of her eye among the crowds. It was the same color as Magister Anodatus’s robes. But he was nowhere to be seen.

She stood there, all senses alert. Perhaps she had imagined it?

Calpernia wasn’t given to imagining things. She quickened her pace. Better to finish her task before she was interrupted.

West of the Proving Grounds she came to a courtyard where, surrounded by gravel paths and manicured bay trees, stood a statue of a ferryman. A stone cat crouched at his feet, and a stone raven perched on his shoulder. Under the hood, the ferryman’s noble, serene faced gazed over the city as he leaned on his pole.

“Avanna, old friend,” she said.

There were many statues of Archon Darinius—founder of the Imperium, magister, prophet, and High King—but this one was special to her. On the day of that mages’ duel when the loser turned to ashes, full of what she had seen and was not able to understand, that blonde child stumbled here and found the statue. She was too young then to know the full story of the man—Calpernia remembered first being drawn to the stone cat—but she felt the presence of Darinius’s power and was reassured. She returned often, speaking her fears and dreams to his stone ears.

Now, at last, Calpernia had something worthier to give him.

She poured her incense into a bowl at the foot of the statue. With a practiced snap of her fingers, she ignited the charcoal brick with a magical spark. Fragrant smoke rose.

Calpernia wrapped her sleeves around her body. The smoke shifted past the statue like waves, as if he was truly poling a boat. Darinius the Ferryman was another of his nicknames, after a vision he’d had at a turning point in his life. Archons today wore the Ring of the Ferryman showing Darinius in this guise, as a symbol of their office.

They have done nothing to earn it.

“You came from nothing,” she said to the statue. “Your royal mother had to hide you from her enemies; you were raised as an orphan ignorant of your heritage. But your magic couldn’t be denied, nor your greatness. In time, you founded an empire. You changed the world.”

She smiled. “And you honored your foster mother all your life. A priestess of Dumat who found you adrift in a basket on the seashore and raised you as her own son. Calpurnia, they called her. I can read her name now. I shall do it honor in turn.”

“You presume to make such a comparison?”

Magister Anodatus was standing at the entrance to the courtyard. Without his usual smirk, his expression was as dark as the curving scar on his cheek. Two heavyset slaves stood on either side, wearing helmets that covered their faces like portcullises.

“I kept thinking, ‘there is a face I know’,” Anodatus said, walking toward her. “Yes. Erasthenes’ thrall, dressed up like a paper doll with a staff she has no right to carry, buying precious incense with coin no slave should have.”

His boots crunched on the gravel. “Your master no longer answers messages sent to his door, and his household is shut. Why?”

“Perhaps he made me his apprentice,” said Calpernia, holding her voice steady. “As for refusing to answer, you know how he likes to shut himself away to work.”

“Or,” said Anodatus, “you have done away with him in his sleep, with the little tricks he taught you, and now you seek to ape your betters.” Light flared from the golden-grained staff he carried. “Erasthenes was a most valuable friend. His knowledge of the Old Gods and their magic was irreplaceable. For him to die at the hands of a slave is insulting.”

His presence pushed out at her, and Calpernia fell back a step, clutching at her own staff. A magister in his full strength was a formidable enemy. Anodatus could boil her bones like water if he chose.

“I didn’t kill him,” she said. “If I had wished, I could have challenged him.”

Anodatus’s glare darkened even further. “You, challenge him? An incaensor, challenging a magister of the Imperium?”

Calpernia’s fear evaporated as that word struck home. Incaensor meant a dangerous substance, like raw lyrium or natron salts. It was slang for a magic-using slave—something dangerous but useful if controlled. If it was broken….

Anodatus swept his staff outwards in her direction. In her fury, Calpernia barely saw the roiling white ball of power that he flung at her as she raised one hand. She felt his attack, and the world around it, and bent her will against it. The ball of power froze in midair, sparkling like a star—and it was effortless.

Calpernia looked past it at Anodatus, who was rigid with shock. In the clear, cold spell-light, she could see the deep wrinkles near his eyes, the slight tremor in his hands, and the fine scars on the slaves that were backing away. Their blood must have been drawn to fuel his magic, she realized. He had sneered at Calpernia’s power, but he needed a slave’s life to augment his own.

With a yell, Anodatus began to cast again, but Calpernia lashed out first with all of her wrath and a tight, intricate sweep of her staff. The captured ball of light ignited into bright golden flame and struck Anodatus’s upraised hands. There was a blinding flash like lightning striking itself, and a foul smell.

When Calpernia could see again, Anodatus was crumpled on the gravel. His hands were gone. In their place were misshapen stumps burned black down to the wrists.

Standing with Darinius’s statue at her back, Calpernia glared at the magister now mewling at her feet. “You have no idea what I am,” she said. “You have never looked down long enough to see what was waiting beneath you. But when the Venatori rise, when a new god burns the Imperium’s corruption to dust, the slaves of Tevinter will walk free in the light. I will see it done!”

She swept past him, stirring the ashes that had once been his hands.

As she strode through the entrance to the courtyard, the helmeted slaves cowered away from her. Despite her glow of victory, Calpernia’s step faltered. Where she’d felt only contempt for Anodatus, there was boundless sympathy for these two. Those helmets hid faces of people with an inner life—and perhaps secret ambitions—as rich as hers. Anodatus had proved to be nothing, but these slaves had never been given a chance to prove they were anything.

“What are your names?” she asked.

The slaves stared at one another, and made no answer. But they stood straighter.

“I meant what I said,” Calpernia told them. “This is only the beginning of the future. If you would see it—shape it—come with me.”

She left. The slaves glanced at the crying Anodatus, at the ashes blowing in the incense-sweetened wind, and then followed after her.