Months have passed and seasons have changed since we released Mass Effect 3—many of which here in Edmonton containing snow—and yet it’s still hard to believe that an entire year has gone by! From beginning to end it has been an amazing experience, and we were so happy to be able to keep Mass Effect 3 alive with additional single-player and multiplayer DLC.

We dove further into Commander Shepard’s adventure with the From Ashes, Leviathan, Omega and Citadel single-player DLCs and introduced new allies and enemies along the way. Players got to meet Javik, the last surviving Prothean, learn more about the origin of the Reapers, and revisit the Omega space with Aria. We also saw an opportunity to expand upon the events at the end of Commander Shepard’s journey with the Extended Cut DLC.

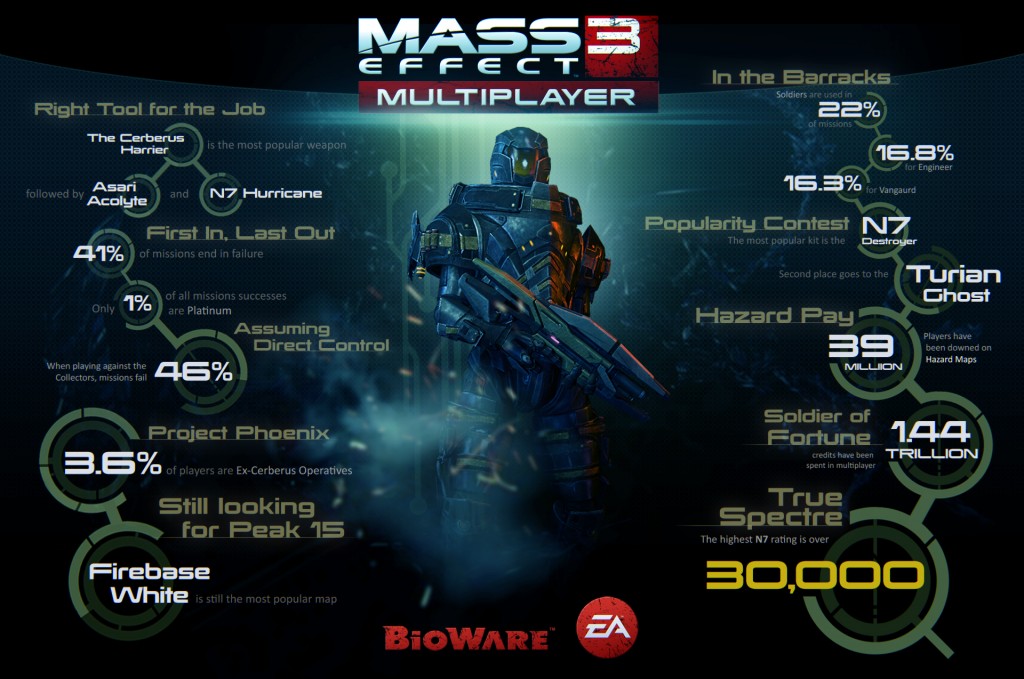

We are extremely proud of the work done by our multiplayer team, who has supported players with five add-on packs and weekly challenges over the last twelve months. Over 40 new kits, 10+ new maps, and dozens of new weapons and upgrades. And let’s not forget the Collectors, and entirely new enemy faction and the return of the dreaded Praetorian.

To help us in celebrating this milestone, our multiplayer team has provided two new updates that we’d like to share with you.

First, is the “Stood Fast, Stood Strong, Stood Together” banner, which can be earned by participating in Operation: LODESTAR and completing the second-tier challenges. This banner features the entire cast of Mass Effect’s multiplayer mode.

Second, is an all-new infographic with updates on the multiplayer war front.

So, on behalf of the team here at BioWare, thank you for making this one incredible year, and thank you for your continued love and support!